Mental Health Professionals As ‘Silent Frontline Healthcare Workers’: Perspectives from Three South Asian Countries

Mental Health Professionals As ‘Silent Frontline Healthcare Workers’: Perspectives from Three South Asian Countries

Sheikh Shoib1, Anoop Krishna Guppta2, Waleed Ahmad3, Shijo John Joseph4, Samrat Singh Bhandari4

Abstract

Mental health professionals across the globe foresaw the mental health impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. They have faced a scarcity of trained professionals, rising morbidities, lack of protective gear, shortage of psychotropic drugs, and poor rapport building because of masking and social distancing. Amidst all, they have responded with approaches that focus on continuing mental health services to the patients already in care, educating the vulnerable people to help them cope with these stressors, and providing counselling services to patients and families affected by the pandemic.

LEAD-IN

The unprecedented impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused a jolt to various realms of life and various groups of people globally. There is a plethora of mental health and psychosocial issues associated with COVID-19. The psychological repercussions of the pandemic in the general population and amongst health professionals may last a long time compared to the acute medical crisis. The enduring outcomes of this pandemic are not yet fully estimated. Early screening of mental health and timely action can go a long way in improving the quality of people affected.[1,2] Mental health professionals across the globe foresaw the mental health impact of such an extraordinary crisis and have responded with approaches that focus on continuing mental health services to the patients already in care, educating the vulnerable people to help them cope with these stressors, and providing counselling services to patients and families affected by the pandemic.

Examples from all over the globe have proven that mental healthcare workers have been on the frontline but, peculiarly, deal with the crisis times. Among other regions in Italy, in Lombardi, Mental health workers provided mental health services to the citizens most severely struck by the pandemic on priority, and providers ensured continuous provision. [3] The psychiatry service in Spain formulated a contingency plan reorganising human resources, closing some units and shifting to telepsychiatry practice, alongside two programmes specifically focusing on the homeless.[4] Comparable changes have been described and suggested in the United States[5] and France[6] to strengthen mental healthcare delivery during challenging times. The United Kingdom Academy of Medical Sciences and Mental Health Charity took the initiative in the early weeks. They suggested the acute need for quality research to discover the vulnerable groups and the effects of COVID-19 on the brain’s functioning.[7] China provided telemental health services, including supervision, training, and psychological services (counselling and psychoeducation) to the people highly susceptible to the infection.[8] In Australia, officials increased the funded services and appointed consultants and specialists, whereas they did not focus on facilitating the people in mental health services.[9] In Malaysia, online counselling services and psychological first-aid were provided to the people throughout the pandemic by utilising reactive support systems.[10]

The authors have, with this, thrown some light on their perspectives on the contributions of mental health professionals as frontline healthcare workers in India, Pakistan, and Nepal.THE REPUBLIC OF INDIA

A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) mentions the Government’s total expenditure on mental health in India as 1.30 % of the overall government health expenditure. The country has only 0.29 psychiatrists per 100,000 people.[11] There is undeniably a shortfall in the quantity and quality of mental health services and their distribution in the country. Another publication estimates the number of psychiatrists in India currently as about 9000 and the number of psychiatry graduates per year as about 700. Based on these estimates, India has 0.75 psychiatrists per 100,000 population, against the preferable number of at least three psychiatrists per 100,000. With 3 psychiatrists per 100,000 population as the preferable number, the study mentions that the number of psychiatrists required to reach the desired ratio in India is 36,000. The country is currently short of 27,000 psychiatrists based on the current population.[12] According to a survey conducted by the Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS), there has been an increase in cases of mental health disorders in India by 20% within a week of the commencement of the nationwide lockdown. The country can anticipate a major mental health crisis resulting from unemployment/loss of jobs, alcohol use issues, financial adversity, intimate partner violence, and monetary liabilities in the subsequent months. The at-risk population comprises around 150 million persons with existing psychological issues, survivors of COVID-19, frontline healthcare workers, youngsters, differently-abled persons, female adults, those working in unorganised sectors/immigrant workers, and older adults. The current need is to construct a community-based capacity to manage local issues long after the acute stage of the pandemic.[13]

Considering the potential of relapse of illness, if psychotropic medications are not made available to patients due to a lack of new prescriptions, society has asked to relax the norms so that patients can get their refills with old prescriptions or through online prescriptions till the crisis is over.[14] The various state branches under the aegis of IPS have made available a list of over 650 psychiatrists who have volunteered to meet the need of the affected population. This voluntary telepsychiatry service will provide psychological support to patients with pre-existing psychiatric conditions and healthcare workers involved in the care of COVID-19 patients.[15]

To assist, educate, and advise psychiatrists towards providing telepsychiatry services as a routine in their clinical practice, IPS and the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) have brought out an operational guide aimed at practising psychiatrists in India as well as low and middle-income countries (LAMIC). This guide covers legal, technology, electronic case documentation, consultation, online prescription, teletherapy aspects, basic minimum standards for documentation, and proformas for ready reference and use by the patients/their relatives/nominated representatives, and the psychiatrists.[16] With practice guidelines and standard operating procedures available, telepsychiatry seems well set for gaining wider acceptance and adoption in India.

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN

In Pakistan, mental health service providers have responded similarly and have faced special challenges. There is a shortage of mental health professionals, with only a few hundred fully trained psychiatrists and almost non-existent psychotherapeutic services. The current pandemic has worsened the situation even further. Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals have responded with various programmes to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of the citizens and the mental health services. Almost all hospitals across Pakistan provide free telepsychiatry services to patients in their respective areas. Similarly, the Pakistan Psychiatric Society has been active in supporting the nation’s mental health, carrying out social media awareness campaigns and making suggestions to the Government of Pakistan to take steps in this direction.[17] The Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, launched a mental health programme for children and adolescents to help and train parents to do therapies at home and enable them to deliver rehabilitation to their children in such needs.[18] Likewise, an Online Mental Health Rapid Response Team started providing counselling to patients from remote areas of Pakistan.[19]

Because of the lack of reliable internet connectivity across the country, especially in rural areas, and low education rates, providing internet-based services has not been without its own problem. The consensus among psychiatrists is that patients have not been seeking telepsychiatry services as expected. Similarly, the response of the Government of Pakistan has been lukewarm.

THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL

The Nepalese society believes that a doctor should always work selflessly despite the pain. Health professionals in Nepal have already been facing anxiety and depression.[20] Lack of personal protective gear, inadequate hospital infrastructure, stigma towards healthcare workers, and lack of governmental preparedness have worsened the already prevalent burnout in a resource-deprived health system.[21-24]

Mental healthcare workers (MHW) face additional hindrances. Uses of masks and social distancing in psychiatry have only blunted the interview and therapeutic effects due to poor rapport and slowed communication.[25] MHWs have been working in a situation where a psychiatric pandemic is looming over. They are known and expected to spend more time than other professionals due to extensive history, psychotherapy, and counselling. They are expected to listen patiently and lend tissue to weeping patients daily during a pandemic or later. Thus, limited contact or exposure is impractical.

Most of the psychiatrists in Nepal are known to serve through satellite clinics. They have not been able to continue that since the Government implemented the country-wide lockdown on March 24, 2020.[26] In the absence of consultation, old cases have worsened, and an increased suicide rate during the pandemic.[21] The unavailability of medicines in rural areas has added to the misery. Local pharmacists tend not to provide psychotropic drugs without a prescription. Nepal has only 0.36 psychiatrists per 100,000 population.[27] Amidst this, they have been working without complaining. Additionally, they have used online social platforms and telepsychiatry to serve the needy. Most of the service they offer is for free. The Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal has provided free helpline numbers. Local psychiatrists have volunteered, and each has received up to 30 calls per day! Some have been posting educational videos, while others are attending webinars and discussions on social media intending to alleviate anxiety and combat depression in the general population. Several pages and blogs have been created over the last few months, and the only reward expected is someone being benefited. This has been useful in LAMIC before.[28]

In conclusion, the silently working Nepalese psychiatrists are likely to have increased work after the lockdown is lifted shortly. We suggest task shifting as a handy tool to serve Nepalese remotely located on the rugged landscape. We need to train local community workers and paramedics to assist the overworked MHWs.

LEAD-OUT

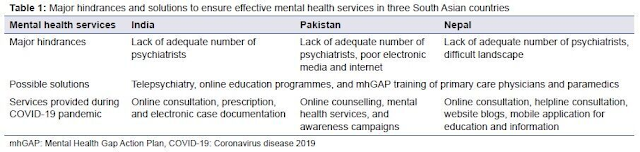

Hopefully, perspectives from these three South Asian countries will take the readers through a roller coaster ride of the role of mental health professionals on the frontline. It highlights the lack of mental health professionals to face the impending psychiatric pandemic. The common hindrances faced by India, Pakistan, and Nepal are poor social connectivity, possible scarcity of psychotropic drugs, and failed outreach clinics. The complex landscapes, especially in the northern part of these three countries, have added to the misery. However, the silver lining that appears to be is telepsychiatry that can make it possible to reach the socially and geographically distanced population (Table 1).

It is also imperative to focus on survivors and healthcare professionals following the pandemic in alleviating the burden of distress in humans. Peer support can alleviate this anguish, encouraging social connections and improving physical safety. Social distancing need not be emotional distancing. Also, there cannot be a better time than now to promote Mental Health Gap Action Plan (mhGAP). Thus, psychiatrists can train local practitioners and primary care physicians to treat and counsel local patients under supervision. This is likely to alleviate mounting stress for mental healthcare workers. Last but not least, the health of MHWs needs to be prioritised by the respective governments to sustain the health system during the psychiatric pandemic that is likely to follow.

About the Authors

1Jawahar Lal Nehru Memorial Hospital, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India, 2National Medical College, Birgunj, Nepal, 3Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences, Peshawar Medical College, Mercy Teaching Hospital, Peshawar, Pakistan, 4Department of Psychiatry, Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences, Gangtok, Sikkim, India

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment

Your Thoughts?